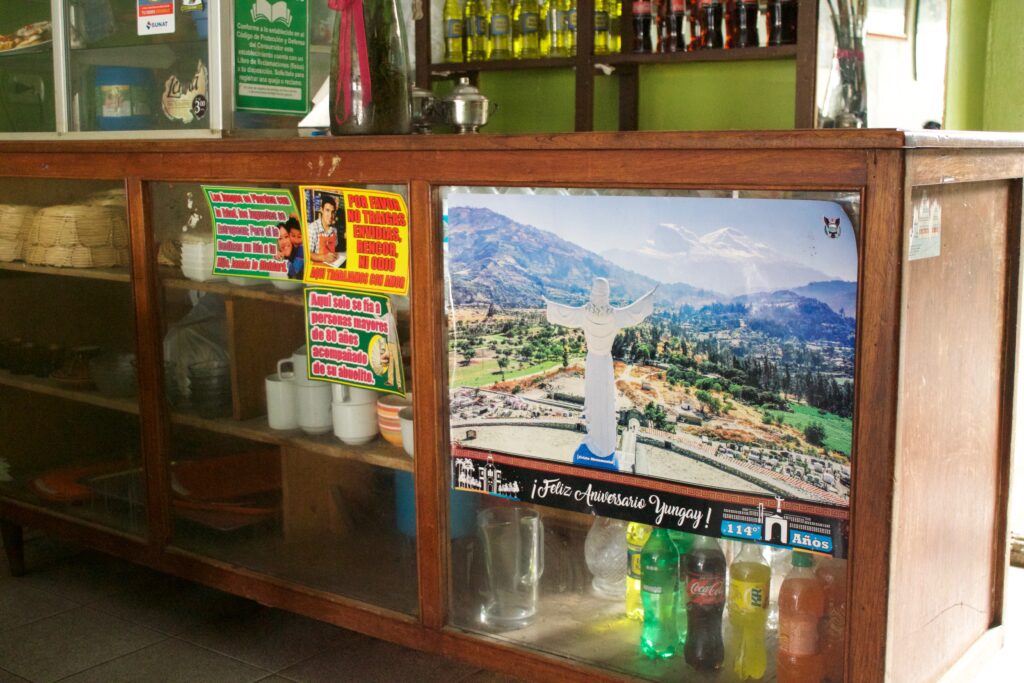

If we understand a place to be its buildings, roads, and houses, then the old Yungay has disappeared. But if place is also made of memories, dreams, and aspirations, then the old Yungay is still existent. Pictures of the old Yungay hang everywhere in the new settlement. The photographs here were taken in homes, hotels, restaurants, shops, schools, and governmental departments.

Most of these images are portraits of the old colonial square. They foreground the whitewashed, neobaroque church, and its surrounding palm trees. In the background stands the majestic Huascarán mountain.

Others are photographs that were taken in the immediate aftermath of the earthquake. They show the trajectory of the landslide from a birds’ eye view or focus on important sites of its mass destruction.

These are depictions of a past that evokes pride and nostalgia. Some of Yungay’s oldest residents dream of old Yungay as the future. They wish that the new Yungay could become what it once was, or what it could have been, before the disaster. They long to recuperate their homes and their lands that were lost after the landslide. Like these images, such desires haunt Yungay like ghostly apparitions or faded possibilities.

But other people remember Yungay as it was with great pain and difficulty. These recollections of Yungay are visceral, and summon memories of misery and mistreatment. Yungay was a place of deeply ingrained social hierarchies and inequalities that functioned on the basis of class, race, religion, and ethnicity. The disaster was hellish, but it also created opportunities for those systematically excluded by this old order. Families were offered houses and work during the initial phases of the reconstruction process.